Re published with permission of Brighton Historical Society

This dressing gown, made from a double bed crazy quilt, shows the work of many hands over many years, from around 1860 to 1915. Initiated by the family of Emerald Hill hoteliers William and Polly Hodgens, the quilt became a communal work featuring contributions from relatives, friends and guests. Together, they filled the colourful patchwork with images and figures from their everyday lives, offering us a unique insight into both the journey of the Hodgens family and the comings and goings of early Melbourne.

Dressing gown, c. 1860-1915 silk, satin, velvet, paper Brighton Historical Society

A journey

Design aspects of this quilt suggest its construction may date from as early as 1860, a significant time period for the Hodgens family. In 1861, William and Emily (Polly) Hodgens married in England before embarking upon a voyage to an unknown future in Australia. News of opportunity in the 1850s Victorian goldfields likely influenced their decision as in 1864 they were living in the Victorian town of Daylesford.

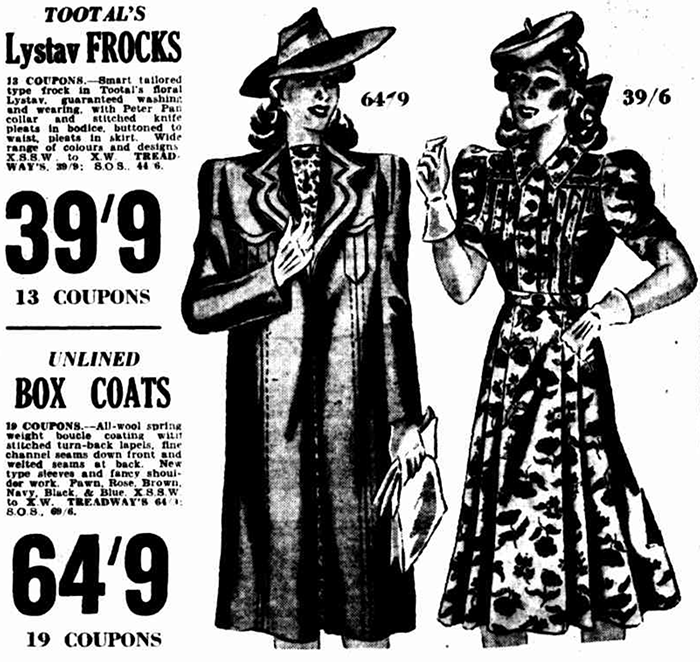

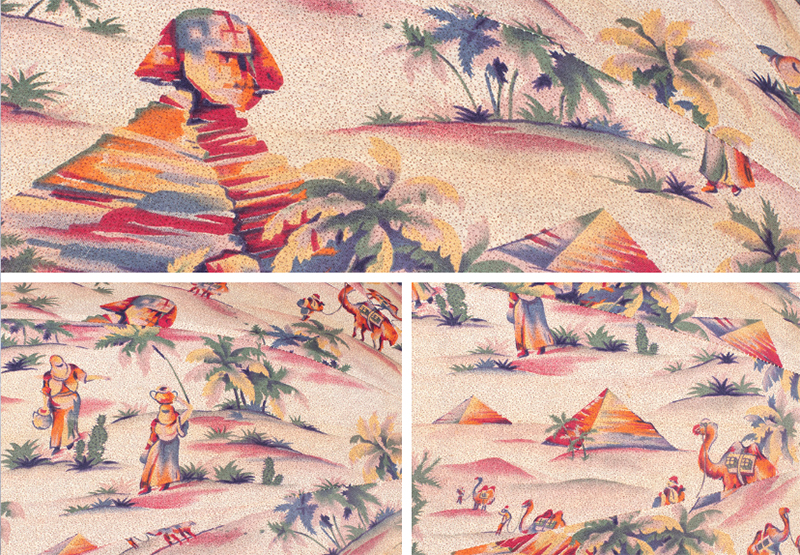

Thousands made the journey to Australia by sailing clipper or auxiliary steamship, an arduous journey of several months. Quilt-making was encouraged aboard ship, the craft having risen in popularity since the 1840s as industrially produced textiles became increasingly affordable. The ‘crazy quilt’ patchwork style became fashionable in the late nineteenth century. These quilts were often constructed of exotic garment remnants such as silk, satin and brocade and embellished with drawing, painting and embroidery.

Left: Franz Xaver Winterhalter, Empress Eugenie of France, 1855 Centre left: Dressing gown detail, portrait of a women with hairstyle of low side buns and dress with open ruffled neckline, painted and embroidered Centre right: Alexander Bassano, Portrait of Edward, Prince of Wales, c. 1871 Right: Dressing gown detail, portrait of a man, ink

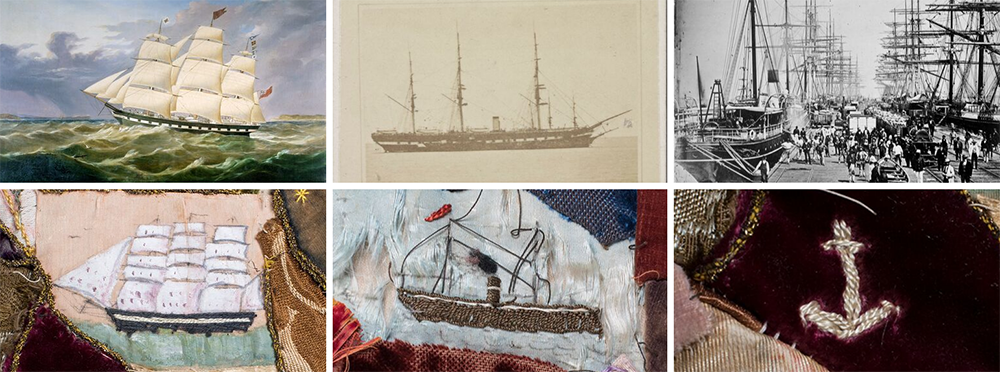

Top left: Thomas Robertson, Marco Polo, 1959. State Library of Victoria Bottom left: Dressing gown detail, sailing clipper, painted Top centre: Paterson Bros. [photographers], Captain Gray and the Great Britain (detail), 1870. State Library of Victoria Bottom centre: Dressing gown detail, auxiliary steamship, embroidered Top right: Charles Nettleton, The Melbourne and Hobson’s Bay United Railway Company’s Pier, 1873. State Library of Victoria Bottom right: Dressing gown detail, anchor, embroidered

Left: John Michael Skipper, Lola Montez (“Spider Dance”), 1855. State Library of South Australia Centre left: Dressing gown detail, an embroidered figure reminiscent of Lola Montez Centre right and right: Dressing gown details, depictions of dance and music

We know little about the Hodgens’ life in Daylesford, but one infamous figure of the goldfields is seemingly represented in the quilt: an embroidered dancing woman bears a resemblance to international star of the stage Lola Montez. Lola arrived in Sydney in 1855 for a yearlong tour of Australia, including the goldfield towns of Ballarat, Bendigo and Castlemaine, where her erotic Spanish-inspired ‘spider dance’ earned her both notoriety and fervent admirers. Dance halls and music were popular respite from the hard labour of gold mining.

New beginnings

Around 1875, with the gold rush in decline, William, Polly and their five children, Emily, Daniel, Ada, William and Mabel had moved to the prosperous, growing settlement of Emerald Hill and established the Adelphi Family Hotel in Ferrars Street, just south of the junction of the St Kilda and Port Melbourne train lines. This close proximity to the train line offered commercial opportunity with access to people, industry and shipping. In 1886 William applied for a victualler license, which would allow him to supply food, beverages and provisions to shipping crews.

Businesses essential to the basic needs of a growing community were soon established nearby, including J. Kitchen & Sons’ soap and candle factory, an abattoir, boiling down works, manure and glue factories. Residential areas were set aside, with low-cost housing constructed. Designed to attract “persons of the artisan class”, “labourers, firemen, boilermakers, mariners and shipwrights”, these “neat two roomed cottages and land” were set upon flood-prone mudflats alive with insects and wildflowers.

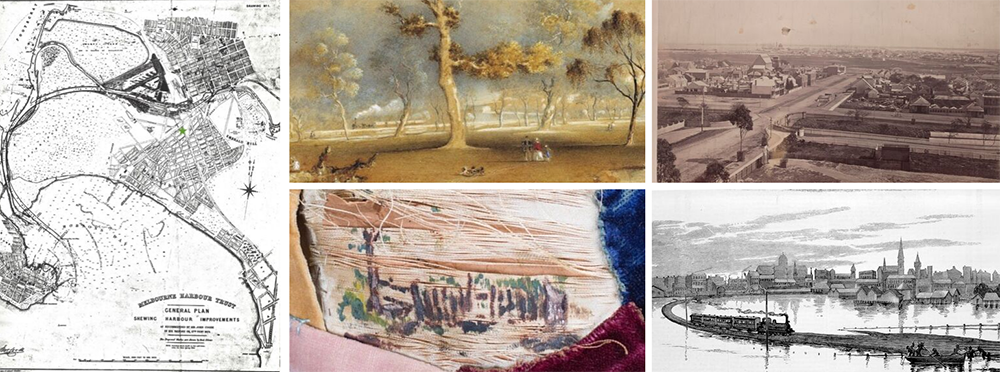

Left: Map of Hobsons Bay and central Melbourne area, 1879. The location of the Adelphi Hotel is marked with a green star. Melbourne Harbour Trust, Works of improvement recommended by Sir John Coode in his report of 17th. Feb. 1879. State Library of Victoria Centre top: William Burn, Train to Sandridge Port Melbourne (detail), 1870, La Trobe Picture Collection. State Library of Victoria Centre bottom: Dressing gown detail, a painting, apparently of a landscape of trees with a house visible between two convergent picket fences Top right: Photo, Emerald Hill and Sandridge, South Melbourne, c. 1875. State Library of Victoria Bottom right: Julian Rossi Ashton, The Floods, 1880, wood engraving. State Library of Victoria

Dressing gown details: Wildlife, domestic pets and wildflowers in and around Emerald Hill

Life and community in Emerald Hill

By 1883 William and Polly had nine children. The last four, Alfred, Helen, August and Eulalie, were born in Emerald Hill after 1875, with little Helen passing away in her first year. The completed hotel offered ten rooms for guests in addition to those occupied by the family and staff.

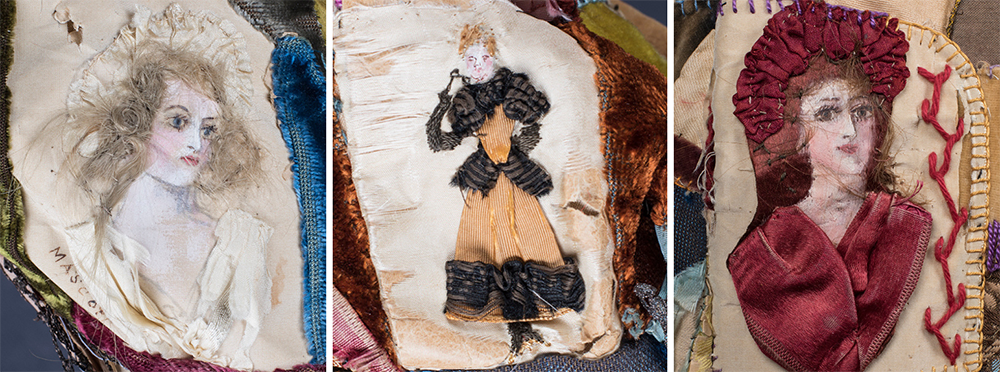

In following years, the family’s daughters invited friends and guests to contribute to the continued creation and decoration of the quilt, recording people, events and surroundings. Particularly striking are several painted portraits, which are credited to daughter Ada Hodgens and feature human hair.

Far-flung countries are represented and bereavements and celebrations recorded. When two Hodgens sons established a brewery business, “Bravo”, in Warrnambool around 1896, the occasion was marked with several embroidered patches – as was the appearance of Halley’s Comet, on its 75-year visitation cycle, in 1910.

Dressing gown details: portraits of women

Top left: Pan-Slavic flag (c. 1848-1918) Bottom left: House flag, Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company, (c. 1847-1914) Centre: Two Swedish flags Top right: American flag Bottom right: American flag image reversed to show correct orientation Inset: Punch, “Souvenir and Official Programme: American Fleet Reception”, 29 August 1908. Public Record Office Victoria

Left: Woman at work Centre left: Ink illustration of a fisherman Centre: Ink illustration of a man Centre right and right: “Bravo” beer

Dressing gown details Left: Cupid, embroidered Top centre: Inscription, “Memory of Our Charming Friend M.H.Coalfleet 11/7/[18]94” Bottom centre: Inscription, “Little Stuert 11.7.[18]94” Top right: Halley’s Comet, embroidered Bottom right: Shooting star, embroidered

The close of an era

Records show that Polly Hodgens remained in charge of the hotel as late as 1913. She died soon after in 1915, with William following in 1916. Family lore states that around this time the pub was sold to the Railway Corporation as part of further rail development. The quilt was passed through the family, reinvented into a dressing gown in the 1970s, before ultimately finding its way to the Brighton Historical Society archives.

The legacy

Through an act of shared craft, we get a sense of how individuals might have connected within a community. In this way, a simple quilt becomes a record of belonging to a certain place in time, a gift to the future offering an image of early Melbourne.

Annabel Butler, 2019

Adapted page design for Brighton Historical Society by Jessica Curtain

References

‘Announcements’, The Australasian, 1 December 1883, p. 11, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/138647594

‘History of Rail in Australia’, Australian Government: Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Cities, and Regional Development, https://www.infrastructure.gov.au/rail/trains/history.aspx

‘Victorian Railway History 1839 – 1899’, Australian Railway Historical Society Victorian Division Inc, https://www.arhsvic.org.au/rail-history/victorian-railways-history-1839-1899

‘Victorian Railway History 1900 – 1924’, Australian Railway Historical Society Victorian Division Inc, https://www.arhsvic.org.au/rail-history/victorian-railways-history-1900-1949

Brick, Cindy, Crazy Quilts: History, Techniques, Embroidery Motifs, Voyager Press, St Paul, 2008

Capper, John, The Emigrant’s Guide to Australia, George Philip & Son, Liverpool, 1853, excerpted at State Library South Australia, http://www.slsa.ha.sa.gov.au/BSA/1853ImmigrantsGuide.htm

Carroll, Brian, Melbourne, An Illustrated History, Lansdowne Press, Melbourne, 1972

City of Port Phillip , ‘History of Port Phillip’, City of Port Phillip Heritage, https://heritage.portphillip.vic.gov.au/People_places/History_of_Port_Phillip

City of Port Phillip, ‘Montague the Lost Community’, City of Port Phillip Heritage, https://heritage.portphillip.vic.gov.au/People_places/Significant_places_in_Port_Phillip/Montague_The_Lost_Community

Dabbs, Christine, Crazy Quilting: Heirloom Quilts: Traditional Motifs and Decorative Stitches, Rutledge Hill Press, England, 2000

‘Arthur Wesley Hughes’, Discovering Anzacs, https://discoveringanzacs.naa.gov.au/browse/person/220130

Gilmour, Joanna, ‘You Beauty’, National Portrait Gallery, 1 September 2010, https://www.portrait.gov.au/magazines/37/you-beauty

Grogan, Robert, ‘A brief history of South Melbourne’, Streets of South Melbourne, 2007, https://streetsofsouthmelbourne.wordpress.com/a-brief-history-of-south-melbourne/

Montano, Judith, Elegant Stitches: An Illustrated Stitch Guide and Source Book of Inspiration, C&T Publishing, California, 1995

‘Journeys to Australia’, Museums Victoria, https://museumsvictoria.com.au/longform/journeys-to-australia/

‘Sandridge Railway Trail’, Museums Victoria, https://museumsvictoria.com.au/railways/pdf/sandridge_railway_trail.pdf

‘Crazy quilt no. 913AK’, National Quilt Register, https://www.nationalquiltregister.org.au/quilts/crazy-quilt-23/

‘The “Night Owls” on Tour’, Prahran Chronicle, 25 April 1896, p. 4, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/165213797

Public Record Office Victoria, ‘Railway Pier c1872’, Flickr, 4 August 2015, https://www.flickr.com/photos/public-record-office-victoria/20084152278/

‘Emerald Hill Police Court’, The Record and Emerald Hill and Sandridge Advertiser, 29 December 1876, p. 3, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/108500000

‘Annual Licensing Meeting’, The Record and Emerald Hill and Sandridge Advertiser, 5 December 1879, p. 3, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/108501818

Sands & McDougall’s Melbourne and suburban directories

Sovereign Hill Museums Association, ‘Lola Montez and her Notorious Spider Dance’, Culture Victoria, 2011, https://cv.vic.gov.au/stories/a-diverse-state/lola-montez-star-attraction/lola-montez-and-her-notorious-spider-dance/

‘Shipboard: the 19th Century emigrant experience’, State Library New South Wales, https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/stories/shipboard-19th-century-emigrant-experience-2

‘Vicfix: Halley’s Comet’, State Library Victoria, https://www.slv.vic.gov.au/contribute-create/vicfix/halleys-comet

‘St Kilda Railway Station (Former)’, Victorian Heritage Database, 2008, https://vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au/places/66553/

Victorian Post Office Commercial Directory, 1891-2

Waugh, Andrew, ‘Victorian Railway Maps 1860 – 2000’, Victorian Railways Resource, http://www.vrhistory.com/VRMaps/.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a Local History Grant from Public Record Office Victoria.

Brighton Historical Society Costume Collection Project, 2018-2019.

Originally published at www.brightonhistorical.org.au 20 October 2019